This article is a preview from the Summer 2019 edition of New Humanist

I’d forgotten the existence of spoon-bender extraordinaire Uri Geller before he pledged to stop Brexit with his telepathic powers in March. The general reaction was lukewarm amusement. In our post-truth era, bending a spoon on camera, or even claiming to have burst the water pipes in Parliament, as Geller also did, feels simultaneously dreary and deranged.

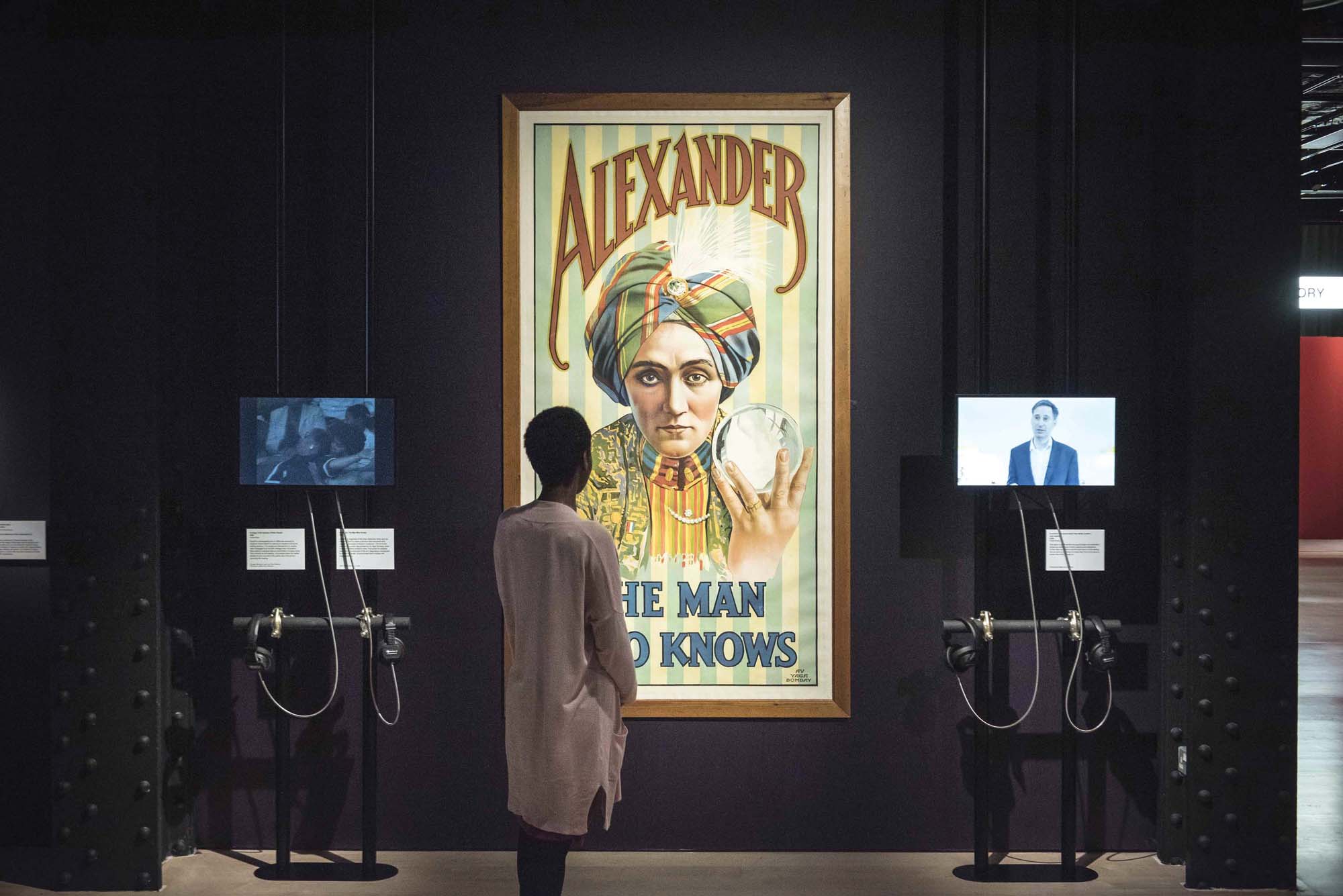

Magicians seem like an odd breed these days. The profession is notoriously male, conjuring the image of a suited Ken doll: part cultist, part used-car-salesman. The exhibition Smoke and Mirrors, now showing at the Wellcome Collection in London, turns these assumptions on their head. Once again, the Wellcome has succeeded in fulfilling its mission to provoke us into thinking more deeply about the connections between science, life and art. It shows us how, in the information age, we have much to learn from the “magical arts”, as our ancestors have done throughout the ages. It is also seriously fun.

Smoke and Mirrors begins in the Belle Epoque of western Europe in the late 19th century, showing us how the development of psychology involved professional magicians. We are plunged into the hazy world of late Victorian spiritualism. Glass cabinets gleam with the paraphernalia of the parlour séance. A foot-long trumpet, designed to amplify the dead, stands opposite a series of spirit photographs, in which life-like plasmic blobs appear to leer over petticoated ladies.

The craze provoked a scientific backlash. In 1882, the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) was born, headed by the utilitarian philosopher and economist Henry Sidgwick. The stated purpose of the SPR – an institution that still exists today, although much transformed – was to test paranormal claims, under strict scientific conditions.

This is where the tale gets its twist. In order to test the mediums, the SPR enlisted the help of stage magicians, illusionists and conjurers. Smoke and Mirrors explores this topsy-turvy battle of wits. Almost a whole room is dedicated to the famous attempt to expose Mina “Margery” Crandon, a medium who gained mass popularity after the Second World War. She was pitted against Harry Houdini, the virtuoso stunt man who had recently wowed audiences by making a full-grown elephant vanish from the stage of the New York Hippodrome. Two of the other judges were high-profile members of the American Society for Psychical Research. But the results were disputed, causing a major rift in the Society.

* * *

These clashes weren’t just entertaining, they were scientifically productive. The SPR was criticised for including spiritualists within its membership, but it also generated some basic methodologies integral to research practice today. They are credited with conducting the first experiments investigating the psychology of eyewitness testimony, and they also developed randomised study designs.

Today, we increasingly understand that humans are terible observers. As the popular neuroscientist Beau Lotto puts it in his recent book Deviate: The Science of Seeing Differently (Hachette): “The world exists. It’s just that we don’t see it. We do not experience the world as it is because our brain didn’t evolve to do so.” Deviate explores the fact that around 90 per cent of the information that we use to see isn’t fed to the brain from our eyes. We perceive mostly during periods when our eyes are fixed upon something. Our brains construct the rest of our visual world, filling in the gaps.

Magicians and illusionists exploit this paradox. Smoke and Mirrors offers a programme of live performances exploring perception and deception. I saw Dr Matthew Tompkins, a magician-turned-experimental psychologist whose book The Spectacle of Illusion: Magic, the Paranormal and the Complicity of the Mind (Thames & Hudson) accompanies the exhibition. He explained how modern psychology is indebted to the “magical arts”, while performing tricks and explaining them, gleefully breaking the magicians’ code. In one deceptively simple trick, he showed four cards and asked us to pick one. “Concentrate on that card,” he said. I chose the Queen of Hearts. “I will now take away your card.” Ta da! The card had disappeared. How had he known?

He’d changed all four. This classic trick relies on my belief that I’d taken note of all of the cards. It depends on me feeling smarter than I am. “Change blindness” is the term now used for the difficulties we tend to experience detecting significant visual changes, even when we are directly focused on a scene. I’d heard of the phenomenon. I also knew that our conscious experience lags about a tenth of a second in the past. Yet I was also flabbergasted. “It doesn’t mean you’re broken or stupid,” Tompkins said. “Your perceptual systems and cognitive systems are weirder than you might think. And that’s important.”

* * *

It is important because our cognitive weirdness is being exploited every day. While Smoke and Mirrors tiptoes around politics, it does include some telling examples of fallible perception and memory. It includes a photograph of Barack Obama shaking hands with the President of Iran, and another of George W. Bush grinning in his car, apparently vacationing with the baseball celebrity Roger Clemens during Hurricane Katrina. Both are doctored images, based on fake news propagated by right- and left-wing channels respectively.

In a 2010 study by Slate magazine, 15 per cent of those who saw the Bush photo claimed to remember having seen the incident, while over a quarter remembered Obama and Ahmadinejad shaking hands.

In a recent interview, the British illusionist Derren Brown explained his craft in these terms: “Even a magician showing you a card trick is just getting you to tell yourself a story . . . you’re being sold a story with particular edit points . . . that’s what life is, we have this infinite data source coming at us and we have to reduce it to stories.” Fake news purveyors and fear-mongering pundits rely on our predictive brain and its need to fill in the gaps. Tucker Carlson of Fox News and Alex Jones of InfoWars are our modern masters of the magical arts. And the machine behind the curtain is becoming ever more sophisticated.

Franklin Foer, the author of World Without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech (Penguin), has described the ability to generate manipulated video as an existential plunge: “We’ll shortly live in a world where our eyes routinely deceive us. Put differently, we’re not so far from the collapse of reality.” Foer is right to worry. Yet a trip to Smoke and Mirrors reminds us that we’ve never been able to believe our eyes. One video at the exhibition shows a man throwing a ball up three times. The third time the ball doesn’t fall back down. You’ve guessed it: the ball doesn’t exist. Like most viewers, I imagined it based on prediction. No AI required.

* * *

In Sacrifice, Derren Brown’s latest Netflix show, he attempts to turn a white American man with strong anti-immigrant sentiments into a hero who, by the end, will voluntarily take a bullet for a Mexican man without papers. Brown has been lambasted for his manipulations, yet Sacrifice poses the question: is his subject being programmed or de-programmed? The conditioning techniques Brown uses are taken to an extreme, but they are also common in advertising. The magician’s method of forcing – getting a punter to pick a card while believing it’s of her own free will – is not so different from that of nudging, a buzzword for politicians and policymakers.

Magic teaches us that seeing is believing. Or, more to the point, that believing is seeing. This is a powerful lesson in our saturated information era. Like a harmless fright at a horror movie, there is a healthy thrill in being fooled. We laugh and clap, coo and blush, moved by the same basic tricks that tickled our ancestors centuries ago. Parts of modern science are indebted to magicians, as Smoke and Mirrors delightfully displays. The exhibition’s more controversial message is that we still have something to learn.